A demand for Drake: What is the value of a single song on Spotify?

If you’re not a fan of Drake… well, bad luck, because you can’t get away from him. In an overly-zealous attempt to promote his new album, Scorpion, Spotify chose to include Drake in every single one of its discover playlists over the launch period. This sparked a backlash from music fans, the likes of which haven’t been seen since iTunes snuck a copy of U2’s Songs of Innocence into its users libraries, with Spotify users demanding refunds for the sudden omnipresence of Drake in their lives.

As the BBC pointed out, Spotify’s promotion of Scorpion was undeniably over-egged, with songs from the Canadian-born musician appearing on playlists titled ‘Best of British’ and every genre known to man. As a result some subscribers to the paid-for Spotify Premium, which boasts a lack of ads as a feature, considered that they were being served advertisements for a single artist with the relentlessness of the T-1000.

While the controversy is perhaps overblown – unlike the Songs of Innocence debacle, which necessitated bespoke software to be developed to remove the album from users’ libraries – it actually reveals quite a lot about Spotify’s business model and, in turn, the business models of the artists whose oeuvre appears on the platform.

Just as has happened with publishers, the rise of digital platforms like YouTube and, later, Spotify and other music streaming services drastically increased the potential audience size for musicians. And, just as with news publishers, those platforms have been the primary beneficiaries of the rush to scale. For context, Spotify alone is now responsible for over 42 percent of all music streaming globally.

Take the non-stop war with YouTube that music labels and distributors have been waging over the past few years, arguing that it both wasn’t doing enough to prevent the uploading of cloned content (which cost them money) and that it wasn’t sharing enough money with those companies. To that end it has recently supplemented its offering with YouTube Music, a new subscription-based service that is designed in part to ameliorate music companies’ fears but which some analysts believe won’t be able to compete with the likes of Spotify or generate enough revenue to keep the primarily ad-funded YouTube happy.

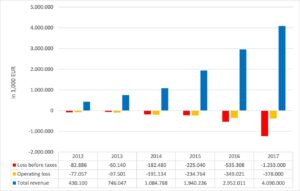

And the musicians themselves were hardly the main beneficiaries of the deal between music labels and Spotify. Until last year, Spotify was reportedly paying out around 70 percent of its total revenues in licensing agreements with labels and the many companies that hold the rights to musicians’ libraries. That was, in part, why Spotify is held up as one of the foremost examples of a platform that has fundamentally upended a traditional business model without turning a profit itself (see also Netflix).

But for all the hype around Spotify’s disruption, it was also ripping up the compact between artists and distributors.

Slim (shady) pickings for artists

For the longest time the musicians themselves didn’t see much of that money – as only around 10 percent of that licensing revenue went to the artists themselves. That was in part why Tidal, the artist-owned streaming service most closely associated with Jay-Z, was formed: To correct that imbalance of value between creator and platform.

And in January of this year, a precedent-setting ruling in Washington bumped the proportion of revenue that went to songwriters and artists to 15 percent. That puts pressure on Spotify, which has suddenly had the relative equilibrium that led to its IPO kicked out from underneath it.

So, in order to deal with that new deficit, Spotify has a few options:

– It can raise its subscription prices (which is undoubtedly coming down the pipe in the next few years, and what other streaming services are counting on in order to court audiences away).

– It can launch its own music label, or accelerate its policy of offering licensing rights to artists directly. While it is primarily focusing this strategy around upcoming and indie artists at the moment, it is reportedly offering deals of 50 percent of total streaming revenue. While that’s obviously less than it offers to the big labels and music publishers, the amount the artists themselves take is considerably higher. The argument is that it is now effectively the three big music corporations – UMG, Sony and Warner Music Group – who keep the artists down. Writing for Wired, Katia Moskvitch says: “The result is an oligopoly that ‘chokes’ the market for artists, because the record labels can operate without the usual rules that apply in highly competitive markets”. Some commentators have argued this is Spotify’s best option – getting into the content creation game, just as Netflix is increasingly doing.

– It can double down on pushing artists it knows are wildly popular to as many people as possible, to hopefully boost the number of streams and ideally, the number of subscribers. In fact, when Spotify actually managed to negotiate down the proportion of revenue it paid to those conglomerates in 2017, it was on the understanding that it continue to increase its subscriber numbers. By boosting Drake to the extent it did, it could in theory seek to capture the members of his huge fanbase.

However, the most obvious reason why Spotify would have pushed Scorpion to the extent it did was because it knew it would dramatically boost the total streams listened to that day. As Variety reports:

“In its first day of release, Drake’s “Scorpion” shattered Spotify’s one-day global record for album streams, according to data on SpotifyCharts.com. According to those figures, the album’s individual track totaled 132,450,203 streams, more than 50,000,000 greater than the previous record, set just weeks ago by Post Malone’s “Beerbongs & Bentleys,” which was streamed 78,744,748 times globally on its first day of release.”

That’s an awful lot of songs against which it can sell ads, and the release did similar numbers on Pandora, Apple News etc. That in turn benefits Drake as an artist, since he takes a proportion of that ad revenue. Back in March, the Wall Street Journal’s Neil Shah argued that this is why artists are releasing an increasing amount of music – quality bedamned – because the streaming economy rewards having a huge library. N.B. the dark side of this is why Tidal reportedly hugely inflated the number of streams some of its star artists received.

It speaks to how fundamentally the music industry has been affected by platforms like Spotify. Whether or not it eventually does launch its own label, which might turn the heat down on artists who feel they have to publish a new album every few months to make ends meet, the value proposition of an individual song has been irrevocably altered.

Martin Tripp Associates is a London-based executive search consultancy. While we are best-known for our work in the TMT (technology, media, and telecoms) space, we have also worked with some of the world’s biggest brands on challenging senior positions. Feel free to contact us to discuss any of the issues raised in this blog.